I’ve always wanted to travel across America. I’ve been a few times, to the major tourist attractions – Disneyworld in Florida, Vegas in Nevada, Cheers in Boston – but there’s so many places I’ve never seen in person, and most likely never will. Fortunately, there’s a solution, and it’s my own personal remedy to all life’s problems: movies. There’s been a movie set literally everywhere. Everywhere! So, this feature sees me cinematically visit a new state every week, through a film that was set there. You can read my journey so far here. Next up: Washington D.C.!

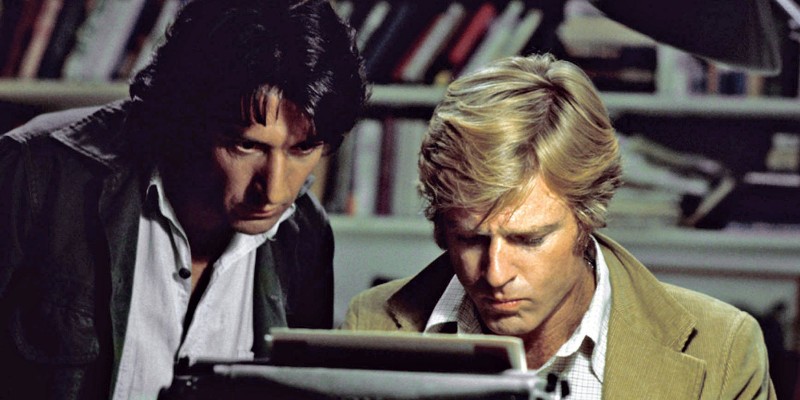

June, 1972. Five men are caught having broken into the Watergate Complex, specifically the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee. Routinely checking out their trial, reporter Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) begins to suspect something may be up through some odd details of the trial, and a shared phone number amongst the address books of some of the accused. Bob’s colleague Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) helps Woodward write a piece on the potential scandal, and the two of them – with the support of their editor Benjamin Bradlee (Jason Robards) and a highly secretive and selective informant known only as Deep Throat (Hal Holbrook) – dig ever further into how far this story goes.

The main problem with not living in America is missing out on a lot of historical and pop cultural essentials. Actually, the main problem with not living in America is we don’t have Taco Bell, but this isn’t a review of Demolition Man, so that doesn’t really fit the subject of this piece. There have been many major events within America’s relatively short history that are internationally noteworthy enough for film-makers to assume a degree of knowledge from the viewing audience, but which I know little about due to them not being part of my History lessons in school, as we dealt with out own much lengthier history. This means that when I sit down to watch All the President’s Men I find myself at a disadvantage to most of the people it was intended to be seen by. Of course I’ve heard of the Watergate scandal (which I agree should be called Watergategate) that eventually led to President Nixon resigning from office, but really only from it’s brief inclusion in Forrest Gump more than anything else. I’ve not seen Oliver Stone’s Nixon nor Andrew Fleming’s Dick, which is entirely my fault, so most of the details of this film were news to me, and I often found myself more than a little confused as to who was doing what, to whom and why. This being an investigative story makes me feel this may have been the intention, piecing the story together to form a coherent whole, but I feel this would have worked a lot better had I been more aware of that whole before embarking on this endeavour. I had a similar experience recently with Oliver Stone’s JFK, depicting another ultra-famous American event that, due to my nationality, age and ignorance, I knew little about beforehand and struggled to comprehend during.

All that being said, and my own confusions aside, this is a great film and a fantastic documentation of how proper reporting used to be, before today’s culture of so-called reporters aiming to get there first, regardless of whether the information is correct. Seeing the Woodward and Bernstein (who would eventually be referred to by their boss as Woodstein) poring over piles and piles of library cards hunting for some minute yet imperative crumb of information, the futility of which is highlighted by the camera zooming out into nothingness in one of the film’s most beautiful shots just makes me angry that pretty much all of today’s reporting seems to be done via press releases or just re-posting what others have written before.

Despite being second billed, this is Redford’s movie. His Woodward is the main reporter with the hunch at the start of the case, and Hoffman’s Bernstein only jumping in when he re-writes one of Woodward’s articles to punch it up a little and refine the fuzziness. That says a lot about Bernstein’s character, in that he’s not afraid to come off like a bit of a dick if it’s with good intentions and in favour of the overall outcome, and the fact that Woodward agrees that Bernstein’s article is better than his shows their easy willingness to work as a team. Bernstein is abrasive, a little flirtatious and often pushy, whereas Woodward comes off as more understanding when leads and witnesses are less than forthcoming during lines of questioning that could threaten their wellbeing. The story doesn’t need a lot of detail for the characters, it’s more about the case and the conspiracy, so that’s fine. We get little bits here and there – Woodward sleeps with his notebook in his hand, Bernstein is perpetually bumming smokes, that kind of thing – but it’s public opinion that these are the good guys fighting for truth and justice, so move along.

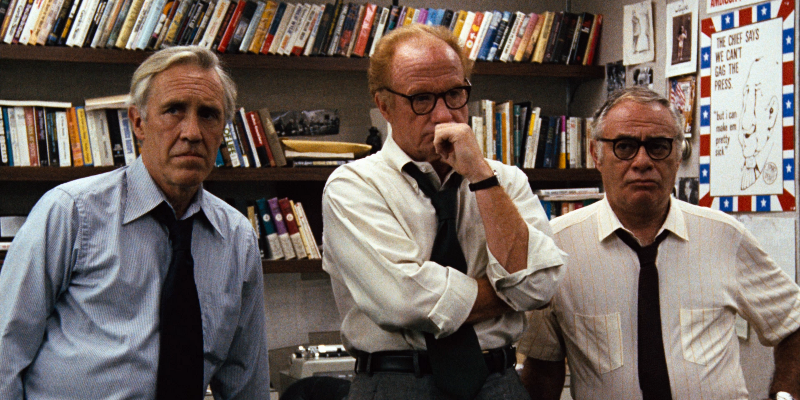

Amongst the slew of Oscars this film received, including Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Sound, is the award for Best Supporting Actor, which went to Jason Robards for playing the editor Benjamin Bradlee. This was a factoid I knew before going in, so I kept an eye on Robards throughout, awaiting the scenes that would explain this award, and alas they never came. Robards is far from terrible, but he’s also not exactly a terribly key figure to the story. He spends a lot of his scenes sat behind a desk preventing Woodstein from printing their most recent article due to a lack of sources. So certain was I that his role would be integral that I thought he might be in cahoots with the scandal, and there’d be some meaty scenes of redemption or confrontation late in the day, but they never came. Robards beat out the likes of Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man, Ned Beatty in Network and Burgess Meredith and Burt Young, both from Rocky, for the award, and I can’t help thinking this was a year it could have gone elsewhere without many batting an eyelid, especially given Robards subsequent win the following year for his role in Julia (beating Alec Guinness in Star Wars? Sacrilege!).

A much more deserving award was that for Best Art Direction/Set Decoration. A great deal of this film is set within the reporters’ bullpen of The Washington Post, and it couldn’t be more of a hive of activity. Regardless of what Woodward and Bernstein are doing – which, for the most part, seems to be phoning potential sources and witnesses, declaring “This is Bob Woodward for the Washington Post…” and leaving a pause for the other end of the phone to be placed back on the receiver – there is always something going on in the background. Theirs is not the only story being written, and given how little of the newspaper is allocated to the story it makes perfect sense for a constant commotion to be occurring all around them. The office itself is resplendent in piles of paperwork, files, typewriters and trays, with knick-knacks, do-dads and lone bicycle wheels strewn everywhere, as you’d expect in a busy office. It’s believable, realistic and thoroughly deserving of its recognition.

Elsewhere the supporting cast includes minor roles from the likes of Ned Beatty, Martin Balsam, Hal Holbrook and Jack Warden (Warden and Balsam having worked together previously on one my personal favourites, 12 Angry Men), and they all give good, solid performances. Holbrook’s Deep Throat is a touch melodramatic, but there’s pretty much no other way of playing that figure, so that’s fair enough. Overall, this is well worth watching even if you don’t have a lot of interest in the subject matter, but if you’re not familiar with the story make sure you pay attention, or you’ll soon be lost. All investigative reporters should watch this on a monthly basis to make sure they’re doing things properly, if only to pick up tips on how to get people to reveal information long after they’ve uttered the phrase “That’s all I’m going to say.” And that’s all I’m going to say.