I’ve always wanted to travel across America. I’ve been a few times, to the major tourist attractions – Disneyworld in Florida, Vegas in Nevada, Cheers in Boston – but there’s so many places I’ve never seen in person, and most likely never will. Fortunately, there’s a solution, and it’s my own personal remedy to all life’s problems: movies. There’s been a movie set literally everywhere. Everywhere! So, this feature sees me cinematically visit a new state every week, through a film that was set there. You can read my journey so far here. Next up: Vermont!

Dr. Constance Petersen (Ingrid Bergman) is a brilliant psychiatrist, but is lacking in bedside manner. She works at Green Manor amongst some quite sexist male colleagues and has never found love, until the new hospital director, Dr. Anthony Edwardes (Gregory Peck, and I’d love it if in E.R. Anthony Edwards played a Dr. Gregory Pecke, but alas life isn’t perfect) arrives to take over from long-term serving director Dr. Murchison (Leo G. Carroll). Constance and Edwardes become close but his behaviour concerns her, particularly his outbursts whenever he sees dark parallel lines against a pale background and, in digging into his past, Constance discovers that Edwardes may not be quite who he seems.

Alfred Hitchcock is, in my opinion, the undisputed master of wrong-man-on-the-run plotlines, and he always seemed to be looking at new ways of playing out a similar story in new ways. Here, the twist is that the accused man, in this case Peck’s Dr. Anthony Edwardes, may be someone else pretending to be Edwardes, and he may be accused of Edwardes’ murder himself. The problem is he has amnesia, and doesn’t know, so he goes on the run with Constance to prove his innocence, or at least work out who he is, but things get tricky when he becomes scared of exactly what he’ll discover. Constance however is adamant that he must be innocent, and it’s here that I must go into how comically sexist this film is. I know it was made in 1945, and back then the ideas on display were more accepted, but nowadays some of them are just ludicrous. This film comes with such dialogue gems as “Your lack of human and emotional experience is bad for you as a doctor, and fatal for you as a woman,” and “Women make the best psychoanalysts until they fall in love, then they make the best patients.” It is Constance’s refusal to accept the possibility of Peck’s guilt that I found the most troublesome, as despite being a very learned doctor who is respected in her field (albeit respected in a legitimate sexual harassment case kind of way) she still insists on following her feelings rather than her intellect. She believes that deep down she could never be in love with a murderer, and she is in love with him, so therefore he cannot be a murdered. It’s backwards logic at its best. Oh, and one more note of sexism, our hero at one point utters the line “If there’s anything I hate, it’s a smug woman.” This is our male protagonist, everybody. The guy we’re supposed to root for and wonder how good he is, and that line comes out without anybody batting an eyelid.

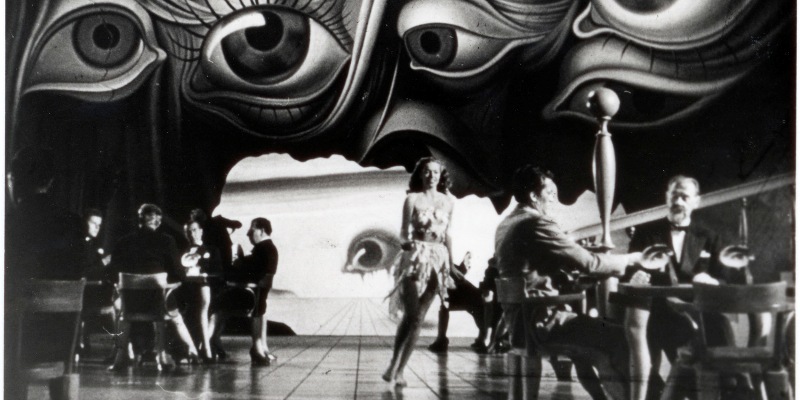

The most infamous scene from Spellbound is easily the dream sequence, predominantly because it’s unlike anything Hitchcock had done before and would do for almost another fifteen years until Vertigo. Here, Constance attempts to delve into Edwardes’ dreams, and we get to experience them too in a very surreal sequence co-created by Salvador Dalí. We get giant eyes on curtains, card games with over-sized blank playing cards, a man running across a bizarre landscape and some very Dalí-esque elements like a melted, deformed wheel. I’d heard this was a particularly memorable sequence, so I was very surprised by how short it ran. Apparently around 20 minutes of dream sequence was created, but it proved too long so we get closer to two. Seeing the whole thing, which is now reportedly lost, would be something special.

Elsewhere there are some more traditional Hitchcock scenes of ramped-up tension, such as policemen looking for Edwardes’ whereabouts standing on an unopened letter that says exactly where he is. A later scene creates a great deal of tension as a flipped-out Edwardes wanders around a home with a cut-throat razor and a crazed expression, but this is one of those scenes that builds to nothing, and as such is a disappointment. It’s immediately preceded by some rare Hitchcock unintentional hilarity with Edwardes, who has awoken in the middle of the night for a drink of water, finds himself freaking out at the colour white, which surrounds him in the bathroom. Everywhere he looks there’s white, on the sink, the bath, the toilet, and it was reminiscent of 1966’s Batman, with Adam West finding a new obstacle every time he tried to dispose of a bomb.

The performances were often melodramatic to a soap opera degree, which was a surprise coming from the likes of Peck and Bergman, but this could have been what Hitchcock was after. If so it’s a questionable choice, as it makes it difficult to care for the plight of these characters, given how prone to over-reaction they are. Still, I enjoyed the plot of a man trying to solve the mystery of his own identity, I just felt that it was often overly sexist and the mid-film “reveal” that there is some doubt as to whom Edwardes might be is built up as a twist, but blatantly so, more so than the overall premise of a film should be.