A personal note before writing this already quite personal post: I haven’t been a very good blogger lately, and I’ve been beating this dead horse so to speak for a couple weeks now as a way of venting my guilt about it. I’m forever grateful to be a part of this amazing site, and it’s almost been a year since I started writing here. This last month or so, I took an unintentional, and thus unannounced, break from blogging. I fell off the face of the earth, and I feel terrible about it.

One reason in particular as to why I felt so terrible—and why I knew I had to snap out of my writer’s funk which was fueled by exhaustion, mainly—was that French Toast Sunday’s director of the month for December was Martin Scorsese. Now, whether or not this gets published in time for Scorcember, I still wanted to write it; because without Martin Scorsese, I may never have started my Trope Talk feature here, and I may never have blossomed into the albeit still-amateur cinephile that I am now, and I may never have found a passion for writing about film at all.

The reason I say all that is because my first of two film classes in college was all about Martin Scorsese—it was designed as a freshman year writing seminar, and everyone had to take one, though the topics and disciplines varied, and I just happened to get into the one whose topic most interested me. This course taught me how to write analytically, especially about film, and simultaneously, it taught me about one of America’s most singular and iconic directors, now one of my favorite directors of all time.

When I think of an auteur, I think of Scorsese, even though the theory—which states that a director can have a personal stamp, namely a distinct style or set of thematic concerns that can be traced throughout his or her films—stemmed from some of Scorsese’s idols: the directors of the French New Wave. Scorsese, as a young boy, suffered from asthma and thus spent much of his youth watching movies, and he also wanted to be a priest at first. It’s funny how much the cinema can influence a person’s interests and goals and outlooks; Scorsese’s films alone have shaped me, mostly in terms of my own viewing practices.

On a separate note, I don’t know to what extent Scorsese is given flack for his arguably increasing awards-show fare, especially considering he didn’t win for the films he arguably should have, finally getting his best director Oscar for The Departed (2006). But I think even within his more flashy films, there’s that spark of creativity—a visual beauty and tone that is so uniquely his—and a passion for innovation. I don’t think he’s lost sight of that after all this time, and sometimes I feel like that’s what’s so commendable about his work and it’s something many might forget; the quality is consistent, but still with a film-student’s flair for experimentation.

That experimentation though is predictable by now, which is in no way a bad thing—I merely mean that you can list the tropes, visually and thematically, that he likes to work with, and you can pick out the films that deviated from that (and probably still find something that ties it to Scorsese anyway). Scorsese’s been known to explore: Italian-Americanism, New York City, the mob/mafia, religion and spirituality, violence and individualism, mental instability, greed and criminality. Aesthetically, he practically color codes his films, sprinkling them with voice overs and tracking shots and dolly zooms. And, let’s not forget to mention those actors he likes to use: Harvey Keitel, Joe Pesci, and of course Robert De Niro and more recently Leonardo DiCaprio.

Besides perhaps Tarantino, who is maybe too on-the-nose an example, Scorsese is the best modern filmmaker to look at auteurism as both a viable theory and something that is wonderfully fraught with tension, too— what do we do with The Age of Innocence (1993) or Kundun (1997)? Do they merely fit in with his historical streak, which also includes The Aviator (2004) and Gangs of New York (2002)? The Venn Diagrams could be endless; you could create a connect-the-dots puzzle with Scorsese’s filmography, and still find tangles and tangents.

Given all that, Scorsese also serves as one of the few directors whose films are commercially successful and entertaining to masses and in some cases considered undisputed classics (like 1980’s Raging Bull or 1976’s Taxi Driver), while also being rich with potential for analysis; let’s talk about the controversy over glorification of bad behavior in both Goodfellas (1990) and Wolf of Wall Street (2013), or whether his female characters are weak and one-dimensional and underdeveloped, or even his choice and use of music. The opportunities are nearly endless, because his films are just that interesting, particularly when positioned against one another, and within film history at large, too.

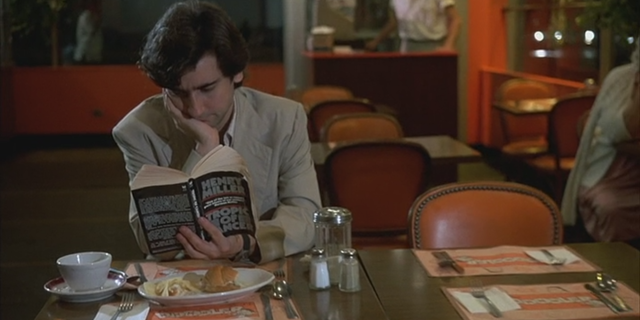

This post had very little direction, and maybe that’s a result of my writer’s block still wearing off. But it could also be because, no matter how many times I write about Martin Scorsese and his films—which, by the way, has been a lot over the last few years—I still find myself overwhelmed by his talent and by his relatively varied work: I mean, not enough people talk about The King of Comedy (1982) or After Hours (1985) or Bringing Out the Dead (1999), right? The first film I ever saw of his was actually Shutter Island (2010), and this film was still enough to start me on a journey of film education both in the classroom and out. Again, there’s so much I could say, and so much I’ve already said in other pieces and essays I’ve written, that I find myself using this space to just reflect on what Scorsese means to me, and how much his films will continue to mean for film fans, film critics and filmmakers for years to come.