Trope Talk is my way of dishing out and breaking down the timeless and the tiresome of cinema’s most recognizable tropes, archetypes and formulas. This month, I’ll be exploring space! Well, not really, but space movies, and even that is too vast a frontier for me tackle. But, with 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) being one of the cinema’s most beloved and renowned space movies directed by none other than FTS’ director of the month, Stanley Kubrick, and with Christopher Nolan’s newest release, Interstellar, having just come out recently, I started thinking about just a handful of space movies and their tropes.

As I said in my little introduction, space in film is always depicted as this beautiful and terrifying thing for us puny humans, and likewise, the films that depict this… well, there are just too many for me to consider them all, making this topic a bit daunting. But, after seeing Interstellar earlier this month, I began to consider all the tropes of a typical space movie— as well as those that an atypical space movie might exclude.

Let’s start with that idea, actually— the idea that a film like Interstellar would exclude certain space movie tropes. I can talk endlessly about Nolan’s wanting to do more than just reinvent the wheel with this movie— in my own review of it, I explained how the film felt like it was missing something or had fallen short, because its intentions seemed so much grander than the final result. But, what I will say is that the story honed in on certain things that are not often explored so deeply or as interestingly in other films about space exploration. For instance, Nolan is particularly interested in issues and conceptions of time, which is refreshing and ambitious and often effective— one planet’s minute might be our home planet’s year, making one hour turn into decades.

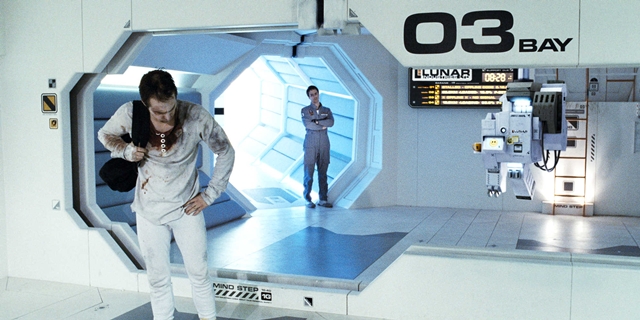

Time is explored to some degree in Moon, as well— Duncan Jones’ far too underrated sci-fi indie from 2009. Sam (played by Sam Rockwell) is living out a 3 year stint harvesting energy from the moon in the year 2035. Time is manipulated cleverly when he discovers an unethical truth about the company he works for (I want to spoil it, but just in case this film flew under the radar for anyone, I won’t). Time, in space, is an unknowable and unpredictable thing, and that is often more terrifying than the vastness itself. Plus, in both Interstellar and Moon, the loss of communication with family back home plays an emotionally resonant role that makes this distance in time and space that much greater.

Another thing more terrifying than space itself: technology. Kubrick’s HAL 9000 might be the ultimate artificial intelligence to ever enter orbit and turn creepy, but his is a legacy that has only continued. GERTY (of Moon, voiced by Kevin Spacey) isn’t evil per se, but these robots do all seem to have this tendency of acting as a companion—the only companion— until the mission is compromised in any way. Then, it’s all about self-interest or the interest of the overall goal (as told by whatever corporate power has made these machines in the first place). In the former camp is Wall-E (2008), whose robots are so sentient and aware, they’re able to know they’d be obsolete and unnecessary if humans could repopulate their old planet. This makes them turn relatively evil relatively quickly, and with very little feeling, causing us to remember—these aren’t companions after all. But Interstellar’s robots were, thankfully, another element that existed outside these norms—they were likeable, reliable and interesting, without ever necessarily stealing the show or being too subordinate, either.

So, for all the tropes that there may be—from technical difficulties to technological enemies, and from illogical time to insurmountable expanses of darkness—there is a pretty wide variety of genres that a space movie could be housed within. Wall-E was an allegory for environmentalism and a beautiful feat of PIXAR’s usual creativity and talent. But, it’s also still an animated film and therefore, could be seen as a kid’s movie to some degree. Meanwhile, Interstellar— for all its attempts in trying to be the next 2001: A Space Odyssey (or at least Nolan’s entry into that unbeatable race)—is a philosophical epic, cerebral and visually experimental all at once. Gravity (2014) is a technical marvel and was an Awards season darling; it took the sci-fi out of space and that might have had something to do with its success.

Then, there are plenty of films I haven’t even gotten to yet—comedies like The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005) and hybrid horror classics like Alien (1979). The former takes some tropes along for the ride but it mostly paves its own hilarious path through space. For instance, even its main robot character is a wholly original and utterly ridiculous conception—Marvin, voiced by Alan Rickman, who is literally depressed. This takes a whole new approach to the soft spoken and assumedly serious robots in every other space film. The latter film, meanwhile, added a supernatural source of dread to the already scary reality of being increasingly alone on a space station millions of light years from home. I could devote a whole other Trope Talk to alien movies but Ridley Scott’s classic certainly belongs in the space category as well. After all, this otherworldly terror gave us the all too chilling proverb that in space, no one can hear you scream, proving that anything that would be horrifying anywhere else is extra horrifying in the middle of a gravity-less wasteland of stars and sky and, well, who knows what else.

Maybe there are tropes that I’m missing and films I’ve neglected to include but, like I said, space is a huge undertaking, even with regard to cinema. But I do hope that this at least sparks some further conversation about what genres could house a space movie and what space movies could do differently now than those that have come before— and if they are to stick to the same conventions, what are they and why do they work? I think our curiosity about space makes us hungry for films that feed that curiosity, no matter if the films happen to feed it with sustenance you’ve experienced before in some other package or form. I think space will always frighten and fascinate us in equal measure, and that is why we will always have films that satisfy those two pulls, perhaps so that we never have to venture into the great unknown ourselves— we can always just do it from our seats while eating our popcorn.