Trope Talk is my way of dishing out and breaking down the timeless and the tiresome of cinema’s most recognizable tropes, archetypes and formulas. This month, I’ll be breaking down and re-grouping the films of FTS’ director of the month for August, Quentin Tarantino, tracing his distinct style throughout his filmography while also picking apart what various genre tropes he is both adhering to and re-purposing.

Quentin Tarantino is one of my all-time favorite filmmakers—a mastermind with postmodern sensibilities (as a result of his learning how to make films from watching so many of them in the back of a video store), his movies are often thought of as pastiches, drawing from other genres, directors, cinematic movements and even specific films. But, what makes Tarantino so fascinating and so successful is that somehow, he simultaneously creates something completely new—not merely remixed, that is, but something truly unique, even for all his pop cultural sampling.

Having seen all his directorial efforts with the single exception of his Grindhouse feature, Death Proof (2007), I thought it would be fun to sort the rest of his films and consider them in the following ways: first, categorizing them by what genres they are drawing from, fitting within, or experimenting with, and second, what distinctly-Tarantino elements are there as well (besides the simple fact that so many genres are indeed present in the first place). Besides, Tarantino seems to me to be something more than an auteur, anyway— like only a few other directors I can think of, he seems to serve as a genre classification unto himself.

1) Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994)— Non-linear Crime Stories + Violence, Music and Snappy/Irreverent Dialogue

Tarantino’s first two features prove first and foremost his penchant for violence, but also his tendency to feature that violence in either a mostly off-screen capacity, often paired with the most interesting musical choices possible (such as the iconic, still deeply unsettling ear-cutting scene in Reservoir Dogs, which is accompanied by Stealers Wheel’s 1972 hit “Stuck in the Middle With You”) and/or in a way that is meant to be over-the-top and thus comedic.

Both films also feature seemingly random, banal topics of conversation between characters, and such dialogue has since become some of Tarantino’s most quotable— everything from Royales with cheese to tipping your waitresses (or not). In terms of genre or filmic references, Reservoir Dogs’ choppy failed-heist plot is definitely reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s noir The Killing (1956), and Pulp Fiction is, of course, all about the seedy, pulpy crime novels of yesteryear, even showing one of its characters reading one.

2) Jackie Brown (1997): The Lone Adaptation and Recalling/Reviving Actors’ Careers

Jackie Brown is, to me, the most overlooked, underappreciated Tarantino film, whether because it’s almost a love story (though I would argue that Django Unchained is even more of one) or because it is arguably his least violent, or perhaps because it was an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s novel. But, the one Tarantino-trope it prominently exhibits is his tendency to pick an amazing cast filled with actors that we know and love, some maybe we don’t yet but soon will, and others whose careers he references and thereby reinvents.

For example, in Jackie Brown, he uses Pam Grier’s former status as Foxy Brown to give a cinematic wink to the tradition of Blaxploitation films, while also adding another key layer to the character of Jackie as well; Tarantino even included her former co-star Sid Haig in a courtroom cameo Grier hadn’t been expecting, not knowing he’d be there until they were actually shooting that scene. In Pulp Fiction, John Travolta’s dance scene with Uma Thurman serves as a similar nod to Travolta’s former glory in films like Saturday Night Fever (1977).

3) Kill Bill Vol. 1 & 2 (2003-2004): Kung-Fu, Samurais, Anime and Revenge

The first two films (but certainly not the last) in which Tarantino really delves into the theme of revenge are also two of his most stylistically violent ventures — the Kill Bill saga, essentially one long film broken up into and distributed in two separate parts, in which Thurman’s Beatrixx Kiddo (aka The Bride) awakens from a coma in search of her daughter and those who have wronged her. Each fight scene is particularly heightened by Tarantino’s awareness of and reverence for Asian filmic traditions— from samurai swordfights and a classic Kung Fu movie’s sense of pacing and choreography, to a backstory segment told through Japanese-style animation.

4) Inglourious Basterds (2009) and Django Unchained (2012): German Cinema and the Western— Pseudo-Historical Revenge Fantasies

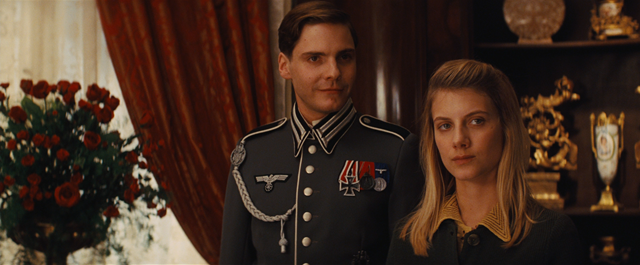

By the time Tarantino’s latest two films came around, he was fully equipped for combining his love of cinema and his explorations of revenge and applying them to two major, not to mention touchy historical contexts, rewriting those histories to give their underdogs a kind of violent retribution only possible on film: Jews during World War II, and Blacks throughout the institution of slavery in the American South. In a way, these two films (my two personal favorites) are the most epic, most violent, most entertaining, and most referential of all his works. Inglourious Basterds is filled to the brim with references: the German Western called Winnetou that is mentioned during the game in the bar scene; the German cinematic tradition of silent ski films; Leni Riefenstahl and a Triumph of the Will–inspired film-within-the-film called Nation’s Pride. And those are just a few of many.

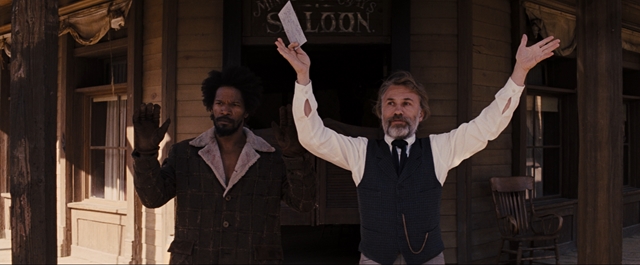

Both of these films take a lot of genre cues from Westerns, specifically Spaghetti Westerns, but Django Unchained— which even opens with the original Django (1966) theme song— is much stricter about those influences; Franco Nero, the legendary actor who played the original Django, even makes an appearance. Django Unchained can also be seen as a “Slavery Epic” of sorts, a kind of melodrama that replaces tears with blood as a physical manifestation of pathos and rewrites the very hero-victim-villain structures of melodrama in such a way so that Django himself, a black man and a slave, is the ultimate hero.

The soundtracks of these two films were, as could be expected, also extremely noteworthy. The use of David Bowie’s “Putting out Fire” in Inglourious Basterds at the point where Melanie Laurent’s Shoshana is seen through graceful, sometimes even aerial tracking shots getting ready to carry out her Nazi-assassination plot, is powerfully ironic and eerily effective. Django Unchained on the other hand benefits from a partially original soundtrack that includes modern hip-hop and a Django-style theme song of its very own—and this is, as far as I am aware, the first of Tarantino’s movies to feature any such original songs.

So, with The Hateful Eight coming to fruition even after a leaked script scandal, and quotes from Tarantino himself about potentially directing a horror or sci-fi feature in the (hopefully) near future, this master of pastiche still has plenty up his sleeve, or shall I say, in his trunk (after all, I couldn’t end this post without at least humorously mentioning his trademark trunk shots). It seems to me that each film of his is even more creative and ambitious and interesting than the last, and with so many other genres and films still left for him to play with and pay homage to, Tarantino is one director whose tricks will never grow stale—on the contrary, I think he’ll never stop fine-tuning the old ones while also never ceasing to discover and come up with new ones.